The Law and Babylon

The Law and Babylon

In her hand, she held a gold cup, full of obscenities and the foulness of her fornication; and written on her forehead was a name with a secret meaning:

Babylon the Great: The mother of whores and of every obscenity on earth

The woman I saw was drunk with the blood of God’s prophets, with the blood of those who had borne their testimony to Jesus.

Revelation 17:4-6, The New English Bible

Apart from the commandments in the Bible, the Law is not written down because it is obvious to any reasonable man that you do your duty to God or your conscience, the first commandment, and you respect the rights of others because you wish to have your rights respected, the second commandment. The Law is not therefore set out in a single constitutional document with articles, amendments and case law. However, the Law and its precedence can be found in different facets of civil law also known as the laws of Babylon:

- written constitutions,

- English case law,

- legalese – the legal definitions of words which vary from their everyday or natural meanings

- the oath

- law books

a

In English statute law

That which seems necessary for the king and the state ought not to be said to tend to the prejudice of liberty of the ekklesia [1]

Any one may renounce a law introduced for his own benefit

Where there is no law there is no transgression, as it regards the world

It is a wretched state of things when the law is vague and mutable

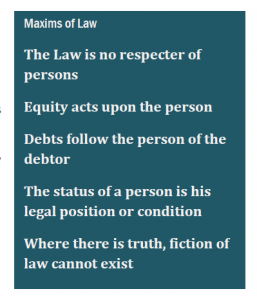

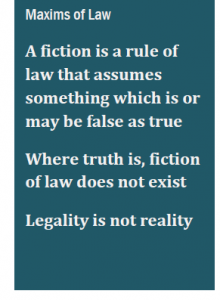

Maxims of Law

a

Legislation and the force of Law

If it is to carry the force of Law in any way, legislation has to be:

- written down and

- clear in its meaning to a reasonable man

It is therefore up to those who believe that UK legislation and case law take precedence over the Law to demonstrate this proposition with reference to written legislation and case law.

However the opposite is true. It is a principle of English law that you can do as you please so long as it is not against the law, which is clearly another way of stating God’s Law or the Common Law:

Everything is permitted which is not forbidden by law

In my rese arch into both the Law and legal codes like constitutions, I have not found a single example or passage that states that a legal code can have a higher authority in law than God’s Law.

arch into both the Law and legal codes like constitutions, I have not found a single example or passage that states that a legal code can have a higher authority in law than God’s Law.

When representing people as a Common Law lawyer, I have drafted letters to official bodies like the Crown Prosecution Service asking them to provide the authority behind legislation. So far none of them has come up with a single reference – let alone an authority – which states that constitutions or statutes take precedence over the Law. Nor have they provided an argument to justify the idea that Acts of Parliament create a binding duty. These communications have though established beyond any reasonable doubt that the CPS – and its parent company, UK plc –is an unlawful corporation repugnant to God and reason. That is my judgement.

In fact, there are good reasons why we should be sceptical about parliamentary legislation. MPs do not vote according to conscience or reason. They vote in the way the government (or opposition) whips tell them. If they indicate that they are to vote against the government’s proposed legislation, they do so under threat from the whips office. Under the New Labour government, an MP was even subjected to violence for stating his intention to vote against a government-backed Bill. Parliamentary legislation is therefore not passed freely. It is passed under duress.

Even if legislation were passed freely according to the conscience of MPs, it does not in itself create a duty. An ‘Act’ of Parliament is just that, an act. Nowhere is an Act of Parliament referred to as ‘law’ or ‘Law’ within its texts. It also comes from a legislature, producing legislation, not ‘Law’. But the UK parliament barely qualifies as an independent legislature because government ministers sit in the House as MPs and like other Members are told how to vote by their parties, robbing the house of the vital and rational debate that is the lifeblood of Truth and Justice.

The historical root meaning of a word can often illuminate its true meaning. The word ‘parliament’ comes from the French ‘parlement’ which means ‘talking shop’, reflecting its ability to only discuss issues and make contractual offers under legislation rather than make binding Law.

The Royal Crest and Motto. The latin version of ‘Dieu et Mon Droit’ is ‘Deus meumque ius’, which is also the motto of the 33rd degree of the Antient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. The 33rd degree is the highest in freemasonry. It is also known as ‘Grand Sovereign Inspector General’

The Sovereign’s Crest

Every piece of UK parliamentary legislation also bears the Sovereign’s Crest, which displays the words:

Dieu et Mon Droit

translated as ‘God and My Duty’; ‘God and My Right’ ‘God is my duty’ – the Law of God in a nutshell — above anything agreed by a vote of MPs (whether under duress or otherwise). Since this is the Law of God, its mention here serves as a reminder of precedence and a contrast to the words of legislation, which are merely a contractual offer which we can refuse according to our duty to God and humanity or our duty to conscience, making the terms of any statute binding only with our consent.

The other motto on the Sovereign’s Crest is:

Honi soit qui mal y pense

This translated as ‘Shame on he who laughs’ or ‘Dishonour on he who thinks badly of this’. In other words, there is only dishonour where ‘Dieu et Mon Droit’ or the Law is not observed.

a

Must, may, shall

Consent makes the law. A contract is a law between the parties, which can acquire force only by consent [2]

Maxim of Law

Anyone who doubts this might like to consider the legal definition of ‘must’, which under its normal or natural definition means ‘to have a duty to’; ‘to have to’; ‘to be compelled or obliged to’. Although the shyster editors of Black’s Law have removed ‘must’ from the 9th edition, previous editions held it to be synonymous with ‘may’.

However, the 9th and latest edition still defines ‘may’ — ‘to be permitted to’ and ‘to be a possibility’ as synonymous with ‘must’:

Loosely, is required to; shall; must […].

In dozens of cases, courts have held may to be synonymous with shall or must, usually in an effort to effectuate legislative intent.

Black’s Law, 9th edition

So in the language of legislation, legislators use the word ‘must’ or ‘shall’ but they do not create a duty because they actually mean ‘to be permitted to’ or ‘to be a possibility’. This means legislation is an offer we can lawfully refuse.

Next time, you get a parking or speeding ticket, study it closely. It usually says you ‘must pay a fine of £x’. In legalese, this means that you ‘are permitted to pay a fine’ or ‘it is a possibility that you pay a fine’. You have no duty to pay that fine. So don’t. Because it all goes to servicing the unlawful national debt, which in turn creates a form of slavery.

In order to prove this, next time you get what looks like a bill, ignore it. Instead, write to the CEO of the corporation concerned asking for a lawful bill of settlement. This must (in its true sense) include:

The amount owed and the lawful reason for liability (like a contract etc).

The name of the man claiming on the liability

His signature

At the same time, enclose a fee schedule stating that unless they have a reason under the Law to make contact or pursue you for money, then you will charge them £x per letter, phone call or other communication. If they then contact you, they accept your contractual offer, sealing the agreement. If they don’t pay your lawful bill, then you can wind up the corporation.

Parliamentary legislation also refers to a ‘person’ rather than a ‘man’. Since the word ‘person’ comes from the Latin and Old English for ‘mask’, it is clear that our person is something we can choose to cast off whereas our status as a man or woman is not. Legalese, a perverted form of English designed to rob law of its clarity and promoted by the Law Society, has over the years tried to confuse this issue.

No matter how Black’s Law defines the word ‘person’, it is still clearly a legal fiction that a corporation can love or perform other duties whereas it is a truth that a man can. A legal fiction cannot take precedence ove r a truth.

r a truth.

- Parliament may intend that we respect its legislation but it cannot put a duty on us to do so, making the terms of legislation optional rather than mandatory, a contractual offer rather than a binding contract.

- Behaviour is unlawful when it violates God’s Law. When it violates statutes like the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act — which made hemp illegal in the UK — an act is illegal.

- In the latter case, it requires your consent to give man authority to act upon you. Just as well really because 200million people are currently starving and 75million die every year as a result of ‘anti-drugs’ legislation across the planet.

Sovereignty of parliament?

It is clear from the above, that the individual man has higher authority than the corporation which is the UK parliament. Some constitutional experts claim that under the UK system of government parliament is sovereign. This clearly does not stand up to independent scrutiny for the following reasons:

- parliamentary legislation cannot have any lawful basis whatsoever without assent from the Sovereign.

- The Sovereign has the Royal Prerogative, the highest force of law.

- The Sovereign appoints the Prime Minister and all other office holders, including judges, and can dismiss a parliament.

- Ministers, judges and MPs swear an oath to serve the Sovereign.

- Parliament cannot wage war without the assent of the Sovereign.

- Any British subject or citizen has an oath to God and the Sovereign, not to parliament.

It would also be a violation of the Sovereign’s oath before God to uphold the Law, to allow parliamentary statutes or constitutional law to take precedence over the Law of God (see Oaths and Heir of All Things).

This is also supported by a renowned lawyer, Matthew Hale, in his account of the Law published in the 18th century:

The Common Law, and the Judges of the Courts of Common Law, have the Exposition of such Statutes or Acts of Parliament as concern either the Extent of the Jurisdiction of those Courts (whether Ecclesiastical, Maritime or Military) or the Matters depending before them; and therefore, if those Courts either refuse to allow these Acts of Parliament, or expound them in any other Sense than is truly and properly the Exposition of them, the King’s Great Courts of the Common Law (who next under the King and his Parliament have the Exposition of those Laws) may prohibit and control them. And thus much touching those Courts wherein the Civil and Canon Laws are allowed as Rules and Directions under the Restrictions above-mentioned. Touching which, the Sum of the Whole is this:

First, That the Jurisdiction exercised in those Courts is derived from the Crown of England, and that the last Devolution is to the King, by Way of Appeal.

Secondly, That although the Canon or Civil Law be respectively allowed as the Direction or Rule of their Proceedings, yet that is not as if either of those Laws had any original Obligation in England, either as they are the Laws of Emperors, Popes, or General Councils, but only by Virtue of their Admission here, which is evident; for that those Canons or Imperial Constitutions which have not been receiv’d here do not bind; and also, for that by several contrary Customs and Stiles used here many of those Civil and Canon Laws are controlled and derogated. […]

Third, that although those Laws are admitted in some Cases in those Courts, yet they are but Leges sub graviori Lege [3]; and the Common Laws of this Kingdom have ever obtain’d and retain’d the Superintendency over them

The History of the Common Law of England, Matthew Hale, 1713 edition

While MPs continue to allow the budget to be spent on the national debt, parliament is breaking the Law as usury – in this case the payment of interest — is unlawful.

English case law and precedence of the Law

English case law and precedence of the Law

English law is also based on ‘precedent’. Black’s Law 9th edition defines it first as: ‘preceding in time or order’. ‘Precedence’ is defined as: ‘Generally the act or state of going before something else according to some system’.

Coming from the Bible, the Law precedes — in the first sense of ‘before in time’ — any constitutional documents, Acts of Parliament or judicial rulings created under English Law.

In its second sense of ‘above in order or rank’, the Law also takes precedence because:

- the Law’s philosophy comes from a higher authority, God, and is expressed as two ‘commandments’ in the Bible, making it mandatory.

- the duty to God encapsulated in the oath means it carries higher authority than anything apart from God’s Law itself.

- in legislation the word ‘must’ does not confer a duty so parliament does not intend its legislation to be binding.

The Law therefore creates a duty whereas statutes – said to take precedence when interpreting English case law under the principle of ‘parliamentary sovereignty’ — do not.

Black’s second definition of ‘precedent’ refers to judicial rulings — decisions made by a court — and includes guidance from law books on the issue:

A decided case that furnishes a basis for determining later cases involving similar facts or issues. […]

A precedent […] is a judicial decision which contains in itself a principle. The underlying principle which thus forms its authoritative element is often termed the ratio decidendi [4] . The concrete decision is binding between the parties to it but it is the abstract ratio decidendi which alone has the force of law as regards the world at large. John Salmond, Jurisprudence 191 (Glanville L Williams editor, 10th edition, 1947)

One may often accord respect to a precedent not by embracing it with a frozen logic but by drawing from its thought the elements of a new pattern of decision. Lon L Fuller, Anatomy of the Law 151 (1968)

Black’s Law dictionary, 9th edition

So it is the reasoning and principle behind a precedent rather than the actual precedent itself that gives it the force of Law. The ratio decidendi behind the Law is:

- it deals with actual, as opposed to theoretical, harm, loss or injury and then to a man who as a soul incarnated as flesh and blood can really experience harm, loss or injury. (Since a corporation is a piece of paper, it cannot. Nor can it be responsible for its actions). For example, legislation holds that any person travelling over 70 miles per hour in a car commits an offence based on a notional idea that the perceived threat to life and limb is actual harm, loss or injury (even though millions of people do this every day without incident).

- Some will say that if we removed this penalty more would take risks at speed so there would be more harm to life and limb. Others might say if more people prayed they would know the protection of God. Legislation suggests that you need to compensate the state, even where you have caused no actual loss or harm. How mad is that? How far has that legal fiction stopped good men in their tracks and allowed those who cause real harm to escape retribution?

- it is mandatory precisely because it deals with real harm. (Who other than a psychopath or sociopath would wish to harm the rights of a fellow man?).

- it is paramount because it comes from God, a higher authority than man. God’s authority over man is recognised in the oath of office, applicable to any public office holder in the UK and particularly to those with involvement in law enforcement like judges and police officers.

The existence of God is also recognised in commercial or maritime law. Every insurance contract allows for an ‘Act of God’, an event for which no claims will be paid by the insurance company. Since this means you are effectively unable to sue God for causing you loss, it also establishes that the authority of God comes above any right accorded by a contract and is supported by the following maxim:

An Act of God harms no one

The laws of Babylon are therefore subject to the authority of God.

The second commandment of the Law of God, expressed as ‘Love your neighbour…’, is also a precedent in English case law, cited in a famous House of Lords ruling which continues to be quoted in English court cases to the present day.

Donoghue v Stevenson [5], [1932] AC 562

If ever the Law of God and man are at variance, the former are to be obeyed in derogation of the latter [6]

That which is against Divine Law is repugnant to society and is void

Maxims of Law

Commonly known as the ‘Paisley snail’ or the ‘snail in the bottle’ case, Donoghue v Stevenson established that the principle of ‘Love your neighbour as you love yourself’ — otherwise defined as a duty of care – took precedence over any contract. Although the case originated under Scots law, the House of Lords determined that the English law of negligence and the Scots law of delict were identical.

On 26th August 1928, Mary Donoghue drank a bottle of ginger beer, manufactured by Stephenson, which a friend bought from a retailer and gave to Donoghue. The bottle contained the decomposed remains of a snail which were not, and could not be, detected until the greater part of the contents of the bottle had been consumed. She later went into shock and contracted severe gastro-enteritis, which she claimed was a result of consuming the defective ginger beer.

In English law prior to Donoghue it was held that someone could claim damages from someone else where the latter owed the former a duty of care and harmed him through their conduct in breach of that duty. However, it was generally held that a duty of care was only owed in very specific circumstances:

- where a contract existed between two parties or

- where inherently dangerous products were involved or

- where a fraudulent claim had been made.

In Donoghue v Stevenson, the manufacturer claimed that he was protected by privity of contract as there was no contractual relationship between Donoghue — who consumed the contaminated drink which caused her to fall ill — and the drinks manufacturer or even the café owner, as Donoghue had not ordered or paid for the drink herself. (Although there was a contractual relationship between the café owner and Donoghue’s friend, the friend had not been harmed by the drink). Ginger beer is obviously not inherently dangerous nor was fraud an issue.

On the face of it, English law did not provide a remedy for Donoghue. Lord Atkins though adopted the commandment to ‘Love your neighbour…’:

The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer’s question: Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law, is my neighbour? The answer seems to be – persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions that are called in question.

Lord Atkin, Donoghue v Stevenson, leading judgment, 26 May 1932

Although in his dissenting opinion, Lord Buckmaster stated that ‘it is difficult to see how any common law proposition can be supported to formulate her claim’, he failed to mention or deal with the Common Law principle of ‘Love your neighbour…’. Upholding Donoghue’s appeal, Lord Macmillan specifically dealt with this omission quoting Lord Esher in Emmens v Pottle:

Any proposition the result of which would be to show that the common law of England is wholly unreasonable and unjust, cannot be part of the common law of England [7].

This authority in English case law demonstrates that the ‘Love your neighbour…’ principle of the Common Law takes precedence (although it is here referred to as ‘the common law of England’, we have already established that the ‘Love your neighbour…’ principle originally comes from the Bible.

In other words where English law clashes with the Common Law, then English law cedes and the Common Law prevails.

It is therefore enshrined in English case law that the Bible carries higher authority than any contract because:

- the plaintiff was able to sue without contract on the basis of a Common Law principle set out in the Bible and

- a contract did not protect the defendant from the ‘Love your neighbour…’ principle, even though this principle is not written down in English law other than in the Bible.

It therefore follows that our contractual relationship with government — dictated by statute and constitution – cannot take precedence over a principle of Common Law.

- English case law therefore has the authority of a judicial precedent which demonstrates the authority of the Law and the Bible over English law, including any other judicial precedent in case law, and records in writing that which already exists under the Common Law: our authority to reject the contractual offer of a constitution or statute at any time and instead be judged on our duty of care to our fellow man.

In a court of law

Since judges are bound by English case law, then they are duty-bound to put its authorities into practice when considering other cases. Since Donoghue establishes that the Law of God takes precedence over contract, a judge has a duty to ensure that the ‘Love your neighbour…’ principle is adopted over any contract like a statute unless you consent to his legal authority to judge you under statute, which he will try and trick you into.

So when a judge asks you:

‘Do you understand the charges?’

know that he does not mean:

‘Do you comprehend…?’

He means:

‘Do you stand under…?’

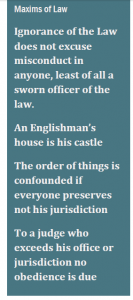

or accept his authority or jurisdiction under legislation. This violates a maxim of Law:

A twisting of language is unworthy of a judge.

And makes any case against the man in question invalid as according to the authority of another maxim:

One is not present if he does not comprehend.

If you consent, you will then be treated as a ‘person’ who can be brought to court by another person or corporation, like the Crown Prosecution Service, under the rules of equity or limited liability [8].

Duty to God and His Law

As well as appearing on Acts of Parliament, the crest of the Sovereign is displayed in every Court room in the land, so the words ‘Dieu et Mon Droit’ are there to remind the judge where his authority to judge comes from: God and God’s representative, the Sovereign – not from parliament, the government of the UK or any constitution.

In other words, when he is under oath a judge has to respect your Common Law rights (see Oaths below) including a defendant’s right of representation by anyone he chooses (rather than it being limited to a ‘qualified’ barrister or solicitor, whose first duty under the civil code is to the Law Society, not to his client [9]).

Under the Common Law, you can sue a judge for failing to respect your Common Law rights. He can also be brought to justice for perjury, failure to observe the oath.

Matthew Hale, in his account of the Law published in the 18th century, comes to a similar verdict:

As the Laws and Statutes [10] of the Realm have prescribed to those Courts their Bounds and Limits, so the Courts of Common Law have the Superintendency over those Courts, to keep them within the Limits and Bounds of their several Jurisdictions, and to judge and determine whether they have exceeded those Bounds, or not; and in Case they do exceed their Bounds, the Courts at Common Law issue their Prohibitions to restrain them, directed either to the Judge or Party, or both: And also, in case they exceed their Jurisdiction, the Officer that executes the Sentence, and in some Cases the Judge that gives it, are punishable in the Courts at Common Law.

The History of the Common Law of England, Matthew Hale, 1713 edition

We often hear the phrase ‘hasn’t got a leg to stand on’ to describe someone who has a case entirely without basis or merit, usually with respect to law. This phrase rather neatly sums up the position of a corporation when it comes up against a man before a judge under oath: a corporation both literally and figuratively ‘does not have a leg to stand on’. Since it is a legal fiction that a corporation can have duties and respect rights while a man really can, a judge has no lawful basis to rule for a corporation over a man.

We often hear the phrase ‘hasn’t got a leg to stand on’ to describe someone who has a case entirely without basis or merit, usually with respect to law. This phrase rather neatly sums up the position of a corporation when it comes up against a man before a judge under oath: a corporation both literally and figuratively ‘does not have a leg to stand on’. Since it is a legal fiction that a corporation can have duties and respect rights while a man really can, a judge has no lawful basis to rule for a corporation over a man.

- Under the Law, a judge only has the jurisdiction to settle a dispute between two men. If you find yourself in court, then insist the judge is under oath (see Oaths below) and that he brings to the court the man claiming injury against you. If he cannot, he has a duty to decide in your favour.

- So-called court orders — based on judicial rulings — are not signed by the judge. As they are not signed, these ‘orders’ cannot carry the force of Law. This is particularly true of a so-called possession order for a man’s house and home.

- If a judge refuses to follow the Law, you can sue him or have him prosecuted for perjury, failure to observe the oath, or for malfeasance in public office or possibly sedition and treason, depending on context.

English constitutional law

Now the promises were pronounced to Abraham and to his ‘issue’. It does not say ‘issues’ in the plural, but in the singular, ‘and to your issue’; and the issue intended is Christ. What I am saying is this: a testament, or covenant, had already been validated by God; it cannot be invalidated, and its promises rendered ineffective, by a law made 430 years later.

Galatians 3:16-18, New English Bible

The UK famously has no single written constitutional document.

The UK famously has no single written constitutional document.

In English law therefore, there is no single legal document which governs the relationship between the rulers and the ruled or defines the rights of the people to allow determination of those rights by a court under a legal system. (The Human Rights Act is an Act of Parliament, not a constitution, and is therefore simply a contractual offer any judge or man can decline to use). In the absence of such a constitutional document, all rights remain with the individual under the Law [11].

In support of this, there are a variety of documents which inform English constitutional law, including Magna Carta, which actually enshrine our rights under the Law and particularly our right to be judged according to God’s Law or the Common Law.

I cannot find a single mention in these documents or elsewhere that man’s rules have higher authority than God’s Law. In fact, a number of maxims demonstrate that God’s Law comes above man.

a

Alfred’s Dome-book

In the 9th century, King Alfred the Great wrote in his famous ‘Dome-book’ – from the Old English for ‘law’ hence ‘free-dome’ or ‘freedom’ — a guide to justice published for the general use of the whole kingdom:

To all who are charged with the administration of public affairs I give the express command that they show themselves in all things to be just judges precisely as in the Liber Judicialis it is written; nor shall any of them fear to declare the common Law freely and courageously.

From the Catholic Encyclopaedia [12]

If we were in any doubt that the Common Law came from the Bible, as part of his exposition of it, King Alfred draws on the biblical ‘Ten Commandments’ as the starting point of interpretation of the Common Law and adds the solemn sanction Jesus Christ gave in the Gospel:

Do not think that I am come to destroy the Law, or the prophets; I am not come to destroy but to fulfill

Alfred also refers to the other biblical expression of the second commandment of the Law in writing:

As ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them […] From this one doom, a man may remember that he judge every one righteously, he need heed no other doom-book.

From the Catholic Encyclopaedia [13]

This establishes beyond any doubt that the Law exists in England prior to the first constitutional document, Magna Carta, and that it has higher authority than any legislation passed by man because by applying its principles anyone can judge anyone else justly without referring to any other ‘doom-book’ or code of laws.

It is therefore clear from this document that the Law takes precedence in England in both senses — in time and rank.

a

Magna Carta

The Law of God and the law of the land are all one, and both favour and preserve the common good of the land

Maxim of Law

The greatest constitutional document of all times — the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot

Lord Denning, English Law Lord

[Magna Carta is the] first of a series of instruments that now are recognised as having a special constitutional status

Lord Woolf, Lord Chief Justice, in 2005

Magna Carta was originally issued in the year 1215 under King John and originally passed into law in 1225. Although there was much dispute over its terms, a version agreed in 1297 still remains on the statute books of England and Wales. It therefore continues to guarantee the rights, freedoms and liberties of the Common Law to all freemen of the realm and their heirs ‘for ever’:

- FIRST, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the Freemen of our Realm, for Us and our Heirs for ever, these Liberties under-written, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of Us and our Heirs for ever.

- THE City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs which it hath been used to have. Moreover We will and grant, that all other Cities, Boroughs, Towns, and the Barons of the Five Ports, as with all other Ports, shall have all their Liberties and free Customs.

- NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right [14].

In this case ‘The Law of the Land’ has to mean the Law of God, which can be guaranteed because it is eternal and unchanging. The phrase was coined to distinguish between the two systems of law in existence, the Common Law and civil law, which includes admiralty and maritime law, so is also known as the law of the sea. This interpretation is also supported by the maxim:

The Law of God and the law of the land are all one, and both favour and preserve the common good of the land

‘The Law of the Land’ cannot be interpreted in its more modern and misused meaning of ‘the collected body of laws of any given country’, because:

- this would be a misinterpretation of the word ‘laws’ which primarily must be interpreted as ‘the two commandments of God’s Law’ before being considered in its misused way where it is falsely held to be synonymous with legislation.

- Legislation is constantly changing. Magna Carta could not insist that anyone be bound by ‘laws’ or legislation yet to be passed in 1215 or 1297.

Any statute repealing these Articles of Magna Carta would by its own definition be unlawful because these rights are part of the Law of God, which takes precedence over any constitution and is recognised as mandatory under the oath.

- The Law pre-exists and is enshrined in Magna Carta.

- Magna Carta did not create the rights of man. It merely codified rights which already existed and were given to man by God.

a

The Petition of Right

On 7th June 1628, King Charles gave royal assent to The Petition of Right, which restated the ancient rights and liberties enshrined in Magna Carta, particularly with regard to habeus corpus, imprisonment only according to fair trial under the Law of the land. In the heated debate leading to the signing of the Petition of Right, the King’s opponents drew on ancient rights and customs clearly based on God’s Law.

The rule of Law and the duty to God central to the Law in the form of the oath are both preserved in two further constitutional documents which prevail over English law, the 1688 Bill of Rights and the 1689 Declaration of Rights.

That oath concerns the joint ‘monarchs’ King William III and Queen Mary and swears allegiance to them and their non-Catholic heirs and descendants.

a

The Oath of the Horatii by Jacques-Louis David, 1784. The ‘oath’ sworn here is not an oath because it honours the Republic of Rome and not God

Oaths and duties

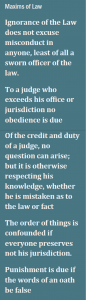

Punishment is due if the words of an oath be false

Maxim of Law

The Oath of Allegiance and the Official Oath are set out in the Promissory Oaths Act 1868:

The Oath of Allegiance

I, NAME, do swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her heirs and successors, according to law. So help me God.

The Official Oath

I, NAME, do swear that I will well and truly serve Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth in the office of […] So help me God [15].

If you swear an oath before God, then it is axiomatic that you are aware that you accept God’s authority – you are effectively asking him to witness your actions and judge you, should you fail to abide by that oath and not be brought to justice by man. If he is able to witness all that you do and judge you, it is clear God has the authority. Once you have recognised God’s authority, it follows that you are bound by God’s two commandments, on which hang ‘all of the Law’.

No man can force another man to swear the oath but any subject or citizen in the UK consents to the oath – by not saying: ‘No’ — and therefore the paramount and mandatory nature of the Law of God. The Sovereign, judges, law officers, MPs and army officers are among those who actually swear the oath before God.

Even though God’s Law is not specifically mentioned in a judge’s oath of office, it does include ‘laws’ which in the context of spiritual matters is most fittingly interpreted as ‘the two commandments of God’s Law’:

Judicial Oath

I, NAME, do swear that I will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth in the office of …., and I will do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm (colony), without fear or favour, affection or ill will. So help me God

And through his duty to the Sovereign, who in turn has sworn an oath before God at their coronation to rule according to Law and Justice:

The Archbishop standing before her shall administer the Coronation Oath, first asking the Queen: Madam, is your Majesty willing to take the Oath?

standing before her shall administer the Coronation Oath, first asking the Queen: Madam, is your Majesty willing to take the Oath?

And the Queen answering: I am willing.

The Archbishop shall minister these questions; and The Queen, having a book in her hands, shall answer each question severally as follows:

Archbishop: Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan, and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and the other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws [16] and customs?

Queen: I solemnly promise so to do.

Archbishop: Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgments?

Queen: I will.

Archbishop: Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? […]

Queen: All this I promise to do.

Then the Queen arising out of her Chair, supported as before, the Sword of State being carried before her, shall go to the Altar, and make her solemn Oath in the sight of all the people to observe the premises: laying her right hand upon the Holy Gospel in the great Bible (which was before carried in the procession and is now brought from the Altar by the Arch-bishop, and tendered to her as she kneels upon the steps), and saying these words:

The things which I have here before promised, I will perform and keep. So help me God.

Then the Queen shall kiss the Book and sign the Oath.

Coronation Oath, Order of Service for the Coronation, 2 June 1953

Since the monarch has sworn to ‘maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel’ then any judge swearing the oath is bound by God’s two laws or commandments through his duty to the Sovereign. If he fails to do his sworn duty under these laws, he commits at the very least perjury, for which the penalties are unlimited, and in certain cases, sedition and treason.

A judge therefore has no duty to parliament and its legislation or the government and its policies and directives, and a binding duty to the Law and the Sovereign who is by oath also bound by the Common Law.

The Book of Hebrews in the New Testament makes it absolutely clear that the oath does not take precedence over the Law.

For the Law appoints as high priests men who have weakness, but the word of the oath, which came after the Law, appoints the Son who has been perfected forever.

Hebrews 7:28, New English Bible

Even if you have sworn an oath before God to serve the Sovereign, you cannot be made to break the Law by that Sovereign (see also Heir of All Things).

a

Clarification of the Oath

Some Christians rightly point out that the biblical Christ warns against the swearing of oaths:

Again, ye have heard that it hath been said by them of old time, Thou shalt not forswear thyself, but shalt perform unto the Lord thine oaths: But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God’s throne: Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King. Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black. But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.

The passage does confirm that the oath exists and is binding because the biblical Christ insists that you will ‘perform unto the Lord thine oaths’. A teaching from the mouth of Christ would — as a rule of thumb — trump all other authority in the Bible. However, this is not the New Testament’s final word on the matter:

For when God made a promise to Abraham, because He could swear by no one greater, He swore by Himself, saying, ‘Surely blessing I will bless you, and multiplying I will multiply you.’ For men indeed swear by the greater, and an oath for confirmation is for them an end of all dispute. Thus God, determining to show more abundantly to the heirs of promise the immutability of His counsel, confirmed it by an oath.

Hebrews 6:13-17, New International Version

As the Book of Hebrews is part of the New Testament; discusses the New Covenant [17]; and acknowledges the arrival of Christ ‘in these last days’, the doctrine presented here cannot be dismissed simply on the grounds that it is part of the Old Covenant. And it is God the Father who was prepared to swear an oath on himself, not a mere man. At the same time, God the Son or Christ claims no man should feel the need to swear to anything even by God. So how do we resolve this apparent contradiction in biblical doctrine?

The most notable aspect of this debate is that both the Book of Matthew and the Book of Hebrews agree on the solemn binding nature of the duty enshrined in the Oath, whether sworn or not. After quoting the old rules, Christ does not say abandon your duty to God, just perform your duty to God without feeling the need to swear it in the presence of another man.

The advice in the Book of Hebrews defends the oath as a way of confirming the truth of a claim, which settles a dispute if the other party will not also swear his truth under oath. Like Christ’s teaching above, it reflects the solemn binding nature of the duty to God, in this case to tell the truth and is backed by two maxims of law:

No one is believed in court but upon his oath

In law none is credited unless he is sworn. All the facts must, when established by witnesses, be under oath or affirmation

The two books therefore disagree only about whether a man can be compelled to swear that oath in the presence of another man. There is no disagreement about the duty to God reflected in the oath, whether sworn or not.

As we have already discussed, a man is bound by the Law of God, and therefore has a duty to God, without swearing the oath. He also consents to the oath by silence.

From further context, the passage in Matthew constitutes Christ’s advice as to best practice spiritually –rather than a statement of rights and wrongs under the Law — as preparation for the New Covenant. Rather than recourse to the Law, in the future you would do better to choose to ignore your rights in favour of the best practice under the New Covenant:

Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth. But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also [18]. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain. Give to him that asketh thee, and from him that would borrow of thee turn not thou away.

The policy of ‘Turn the other cheek’ does not take away your right to self-defence under the Law. God understands that in the heat of the moment you might feel compelled to defend yourself with violence. But the true devotee of the word will allow himself to be struck again and again — rather than do violence — as the best karmic practice. This is just one of a number of seemingly extreme examples Christ uses to illustrate just how important it is to get into heaven (aka the promised land or the New World, post-2012 [19]). Another is the stricture to cut off your right hand if it impairs your chances of redemption [20]. It is clearly not meant to be taken literally.

From context ‘An eye for an eye…’ cannot be read as Christ supporting retaliation —although many people will quote this line out of context to justify it: the next line is the famous biblical exhortation to ‘Turn the other cheek’ and be hit again rather than throw a punch in retaliation.

It is instead a statement on the limitation of damages that can be awarded as compensation, once it has been decided that your rights have been violated because you have suffered loss, harm or injury. An injured man can only sue to recover what he has lost due to harm or injury. Man does not have the authority to award punitive damages or in any way punish another man.

- As the New Covenant takes hold, we should be less and less prepared to swear under oath. God will not though look on you unfavourably, if for example, you swear to the truth of your Common Law rights under oath or need to take to the witness stand under oath. And never ever swear under oath to something you suspect or know to be untrue. That is a violation of one of the ‘ten commandments’: ‘You shall not take the Lord’s name in vain’.

a

Oath-swearers

Every one alive has consented to the oath – to love God and man — by their silence. As international boundaries are fictions to God, then the Law of God and the oath operate anywhere in the universe. In the US, office holders and law enforcers from the President downwards have sworn an oath before God. The same will apply in other countries.

If you want to ensure God’s Law is enforced, then contact an office holder who has sworn the oath. If he fails to help you uphold the Law, he may be charged with perjury and more.

a

Officials/title holders

The Queen is bound by the Sovereign’s Oath.

On the day after taking office, the Lord Mayor of the City of London, travels to the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand, Westminster to swear allegiance to the Sovereign in the presence of the judges of the High Court.

The Oath of Allegiance and Official Oath is taken by each of the following office-holders as soon as may be after they have accepted office:

First Lord of the Treasury (also known as the Prime Minister)

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Lord Chancellor

Lord President of the Council

Lord Privy Seal

Secretaries of State

President of the Board of Trade

Lord Steward

Lord Chamberlain

Earl Marshal

Master of the Horse

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

Paymaster General

Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland (the First Minister of Scotland)

Keeper of the Privy Seal of Scotland

Lord Clerk Register

Advocate General for Scotland

The High Sheriff of each count [21]

The Lord Lieutenant of each county

a

Privy Council

The following oath is administered to Privy Counselors as they take office:

You do swear by Almighty God to be a true and faithful Servant unto the Queen’s Majesty, as one of Her Majesty’s Privy Council. You will not know or understand of any manner of thing to be attempted, done, or spoken against Her Majesty’s Person, Honour, Crown, or Dignity Royal, but you will let and withstand the same to the uttermost of your Power, and either cause it to be revealed to Her Majesty Herself, or to such of Her Privy Council as shall advertise Her Majesty of the same.

You will, in all things to be moved, treated, and debated in Council, faithfully and truly declare your Mind and Opinion, according to your Heart and Conscience; and will keep secret all Matters committed and revealed unto you, or that shall be treated of secretly in Council.

And if any of the said Treaties or Counsels shall touch any of the Counselors, you will not reveal it unto him, but will keep the same until such time as, by the Consent of Her Majesty, or of the Council, Publication shall be made thereof.

You will to your uttermost bear Faith and Allegiance unto the Queen’s Majesty; and will assist and defend all Jurisdictions, Pre-eminences, and Authorities, granted to Her Majesty, and annexed to the Crown by Acts of Parliament, or otherwise, against all Foreign Princes, Persons, Prelates, States, or Potentates. And generally in all things you will do as a faithful and true Servant ought to do to Her Majesty. So help you God.

a

Judiciary

The Judicial Oath (see above) and the Oath of Allegiance are to be taken by each of the following:

Lord Chancellor of Great Britain

Recorder of London

Master of the Court of Protection

Justices of the Peace

Lord Justice General and Lord President of the Court of Session

Lord Justice Clerk

Judges of the Court of Session

Temporary judges of the Court of Session and High Court of Justiciary appointed under section 35(3) of the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions)(Scotland) Act 1990

Sheriffs principal

Parliamentarians

Members of the House of Commons or of the House of Lords are required to take the Oath of Allegiance in the House at the beginning of a new Parliament, as well as after a Demise of the Crown.

Section 84 of the Scotland Act 1998 requires members of the Scottish Parliament to take the Oath of Allegiance at a meeting of the Parliament. Members of the Scottish Executive and junior Scottish Ministers are additionally required to take the Official Oath.

Section 20 of the Government of Wales Act 1998 requires members of the National Assembly for Wales to take the oath of allegiance in either English or Welsh.

a

Military Oath

All recruits to the British Army, Royal Air Force must take an oath of allegiance upon joining these armed forces, a process known as ‘attestation’. Those who believe in God use the following words:

I swear by Almighty God that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, her heirs and successors and that I will as in duty bound honestly and faithfully defend Her Majesty, her heirs and successors in person, crown and dignity against all enemies and will observe and obey all orders of Her Majesty, her heirs and successors and of the generals and officers set over me.

a

Police Oath

I, … of … do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that I will well and truly serve the Queen in the office of constable, with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, upholding fundamental human rights and according equal respect to all people; and that I will, to the best of my power, cause the peace to be kept and preserved and prevent all offences against people and property; and that while I continue to hold the said office I will to the best of my skill and knowledge discharge all the duties thereof faithfully according to law.

As in commercial or constitutional law, ‘law’ (with a small ‘l’) must recognise the Law in order to conform to the Law. In addition, every officer takes the oath to the Queen, who is in turn bound by her oath to the Law. The words of the oath were changed to the current form under section 83 of the Police Reform Act 2002.

Solicitors and barristers are also bound by an oath.

a

The Law and the person

The Law and the person

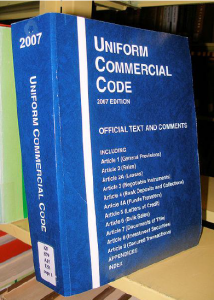

The Uniform Commercial Code

Coming out of maritime law, the Uniform Commercial Code governs contracts, commercial law and the relationships between ‘persons’ (see Legal fiction v reality below) under statute and other legislation [22]. Although it is called a ‘code’ and not ‘law’, it still preserves Common Law rights:

The making of a valid Reservation of Rights preserves whatever rights the person then possesses, and prevents the loss of such rights by application of concepts of waiver or estoppel. UCC 1-207.7

When a waivable right or claim is involved, the failure to make a reservation thereof, causes a loss of the right, and bars its assertion at a later date. UCC 1-207.9

Anderson UCC Lawyers’ Cooperative Publishing Co, 3rd edition

Under UCC 1-207.4, any expression indicating an intention to reserve rights is sufficient. Just state ‘without prejudice to my Common Law rights’, which means that you are only speaking or acting under the Common Law and will not be compelled to perform under any notional contract, constitution, statute or other agreement.

The Code is complementary to the Common Law, which remains in force, except where displaced by the code. A statute should be construed in harmony with the Common Law, unless there is a clear legislative intent to abrogate the Common Law. UCC 1-103.6

Anderson UCC Lawyers’ Cooperative Publishing Co, 3rd edition [23]

In the guidance notes, the UCC itself makes it clear that the Law takes precedence:

The Code cannot be read to preclude a Common Law section.

Even the UCC, the latest codification of civil or maritime law, recognises the Law of God as Common Law and its precedence. UCC1-207.9 can only carry the force of Law with regard to an artificial person, not a natural person or real man (see immediately below). Under the Law, you can choose to opt for your Common Law rights at any time.

a

Legal fiction v reality

Legal fiction v reality

Parliamentary legislation cannot impose a duty on anyone without their consent. It is nevertheless worth examining the real meaning behind the definition of ‘person’, to which legislation refers.

In order to include you in the contract law of statute, the government creates a legal ‘person’ with the same name as you but adding a title like ‘Mr’, ‘Mrs’ or ‘Dr’. (This is usually done by registering the birth with the authorities in return for a birth certificate). For the purposes of determination under English law, this ‘person’ has ostensibly the same status as a corporation. Since a corporation is usually some form of document or register incorporating individual men and women into a society, you as a person also become a piece of paper with notional rights according to maritime, commercial and contract law as opposed to the Law.

Black’s Law has changed its definition of ‘person’ over the years, which has only served to confuse the issue (although a lack of clarity to a reasonable man in written law means that it cannot have the force of the Law). Black’s 3rd edition defined ‘person’ as ‘legal fiction’. The latest edition offers the following definitions:

- ‘human being [24] also termed natural person’

- ‘an entity (such as a corporation) that is recognised by law as having most of the rights and duties of a human being. In this sense the term includes partnerships and other associations, whether incorporated or unincorporated’

- ‘artificial person’, ‘fictitious person’ defined as ‘an entity, such as a corporation, created by law and given certain legal rights and duties of a human being: a being real or imaginary, who for the purposes of legal reasoning is treated more or less as a human being,

- ‘persona ficta [25] [Latin ‘false mask’] Historical. A fictional person such as a corporation’

Black’s Law, 9th edition

Despite the best efforts of the shysters who draft Black’s Law dictionary to confuse the issue, it is still clear that there is a difference between a real man created by God – whether you choose to call that man a human being or a ‘natural person’ — and the ‘person’, a title created by a state with the intention that a man be judged under the same legislation as a corporation — which Black’s Law defines as a fictitious or artificial person, in other words a legal fiction.

The reason a corporation cannot have all the rights and duties of a human being or man – as conceded by Black’s in the definitions above — is that a corporation cannot reject legislation in favour of its Common Law rights whereas a man or a natural person can.

From historical context cited above, it is also quite clear that the person is a role or fiction – a mask — we adopt by consent to be judged under English statute and contract law. The person is no more you than any mask you adopt to play a role. Once you no longer consent to play that role, you cast off the mask or person in a way that you cannot cast off your status as a real man or woman.

a

Persons or corporations under the Law

The Law is no respecter of persons [26]

The status of a person is his legal position or condition

Maxims of Law

The Law of God makes no provision for corporations as they are incapable of love or taking responsibility for their actions. In fact, they display all the characteristics of a psychopath, working solely in their own interest. This manifests as working for shareholder value, in the case of a business corporation, working in the interests of the members in a non-business corporation like a trade union or working in the interests of the central banks in the case of a country or state.

In the context of ‘legal reasoning’ quoted in the above definition, the ‘law’ referred to is clearly legislation rather than the Law. As we have already established, a man can refuse to consent to legislation, which is not binding and is only a contractual offer.

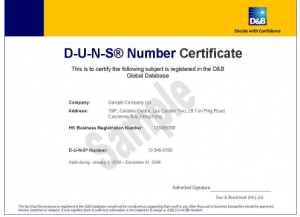

Some will be surprised to find that police constabularies, MPs, government departments like the Ministry of Justice and the UK itself are registered as limited companies on Dunn and Bradstreet’s database of businesses

By this reasoning, the person is a contractual offer made under legislation to which a man can refuse consent, whether the legalese behind the legislation defines him as a ‘man’, a ‘human being’ or a ‘natural person’.

When determining legislation the courts operate under the legal fiction that a piece of paper — or any informal agreement to incorporate – is capable of love, can perform duties or is able to take responsibility for its actions (requirements for determination under the Law) when in fact it cannot.

If you insist that you are a real man — a truth – no one can judge you as a legal fiction. This backed by two maxims of law:

Where truth is, fiction of law does not exist

Fiction of law is wrongful if it causes loss or injury to any one

And if you insist you are not a person, then the judge has a duty to dismiss the case if it has been brought against your person under civil law because:

Consent makes the law. A contract is a law between the parties, which can acquire force only by consent.

Maxim of Law

Consent though is not assent. Remember, consent can be given by not saying ‘No’. This is how a man comes under the authority of legislation. The government will also use your silent consent to the person to induce you to pay their taxes, go to prison, have your children taken off you or otherwise abuse your rights under the Law. (I actually went to prison for telling the truth because I did not know of my Common Law rights at the time). When you consent to this system or code by paying your income tax, you fund government commitments to the national debt and war, rather than welfare or infrastructure.

a

Security and interest

Then saith he unto them, ‘Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s’

While we are on this subject, it is just worth mentioning that the protection of the security of the person — mentioned in constitutions and case law — refers primarily not to your physical safety but to your ability to pay the national debt through taxation — or creating wealth that can be taxed. Under this definition, you act as ‘security’ in the sense of ‘collateral’ — for loans made to the UK government in the same way your house acts as ‘security’ or ‘collateral’ for a mortgage or other loan.

The protection of national security is therefore primarily protecting the nation’s ability to service the national debt, which is unlawful, by collecting taxes. Since MI5 protects ‘national security’ it is a tool of the tax-collectors – who are despised in the Bible.

Babylon has similarly hijacked the phrases the ‘national interest’ and the ‘public interest’. Under the Babylonian accounting system – the system we now live under — the word ‘interest’ refers in the first instance to the interest building up on the national debt. Under commercial rules, the payment of this interest is paramount. Under God’s Law, it is unlawful.

The soldier of Christ serves the common good:

The Law of God and the law of the land are all one, and both favour and preserve the common good of the land.

Maxim of Law

a

In law books

We have already dealt with King Alfred’s 9th century ‘Dome-book’ under constitutional recognition of the Common Law. I now quote and examine other books to demonstrate that as well as being enshrined in English case law and constitutional law, the Law has prevailed and been known to lawyers throughout the history of this island.

The Common Law of England

The Law’s existence and supremacy in the 18th century is confirmed in Hale’s The Common Law of England:

I come now to that other Branch of our Laws, the Common Municipal Law of this Kingdom, which has the Superintendency of all those other particular Laws used in the before-mentioned Courts, and is the common rule for the Administration of common Justice in this great Kingdom. […]

This Law is that which asserts, maintains, and, with all imaginable Care, provides for the safety of the King’s Royal Person, his Crown, his dignity, and all his just Rights, Revenues, Powers, Prerogatives and Government, as the great Foundation (under God) of the Peace, Happiness, Honour and Justice, of this Kingdom; and this Law is also that which declares and asserts the Rights and Liberties, and the Properties of the Subject; and is the just, known, and common Rule of Justice and Right between Man and Man, within this Kingdom.

The Common Law of England, Sir Matthew Hale third edition, 1739, pp 30-31

Blackstone’s Commentaries upon the Laws of England

Blackstone’s Commentaries upon the Laws of England

In his Commentaries upon the Laws of England [27], published in separate volumes from 1765 to 1769, lawyer and law-writer, Sir William Blackstone, quotes Roman author, Aulus Gellius, to show that the Law is of long standing, immemorial tradition ‘expressed in the usage of the people, and accepted by the tacit unwritten consent of men’.

In his Attic Nights, an account of ancient legal systems, Gellius cites the reign of Draco [28], a wise and respected leader who introduced the death penalty for minor offences like theft. Gellius observes that Draco’s harsh laws were abolished, not by order and decree, but by ‘the tacit, unwritten consent’ of the Athenians [29]. In other words, those accused by Draco adopted their Common Law rights to avoid the death penalty rather than reforming Draco’s legal system.

a

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Many things have been introduced into the common law, with a view to the public good, which are inconsistent with sound reason.

A man may obey the law [30] and yet be neither honest nor a good neighbour.

Maxims of Law

While on the subject of the Law’s inclusion in books, we cannot look at this subject without alighting on the numerous attempts to present a false history of the Common Law, particularly by deliberately confusing it with the ‘common law’ (note small ‘c’ and small ‘l’) which originated in the Middle Ages.

The origin of the common law

The English common law originated in the early Middle Ages in the King’s Court (Curia Regis), a single royal court set up for most of the country at Westminster, near London. Like many other early legal systems, it did not originally consist of substantive rights but rather of procedural remedies. The working out of these remedies has, over time, produced the modern system in which rights are seen as primary over procedure. Until the late 19th century, English common law continued to be developed primarily by judges rather than legislators.

The common law of England was largely created in the period after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The Anglo-Saxons, especially after the accession of Alfred the Great (871), had developed a body of rules resembling those being used by the Germanic peoples of northern Europe. Local customs governed most matters, while the church played a large part in government. Crimes were treated as wrongs for which compensation was made to the victim.

This definition from the Encyclopaedia Britannica cannot refer to the Law or Common Law (capital ‘C’, capital ‘L’) as we have already established that the Law exists prior to the Norman Conquest of England as attested to by:

- the Bible

- King Alfred’s ‘Dome-book’, which is alluded to above without mentioning that Alfred has held the Common Law to be paramount and mandatory [31]

- Blackstone’s Laws of England

- The Roman Aulus Gellius describing events in Ancient Greece

- Hale’s the Common Law of England

It also contradicts the Catholic Encyclopaedia’s entry on the Common Law:

It is a source of profound satisfaction to Catholics that it came into being as a definite system and was nurtured, and to a great extent administered, during the first ten centuries of its existence by the clergy of the Catholic Church.

From the Catholic Encyclopaedia

It may not be as clearly drafted as it might be with regard to the first ten centuries of ‘its existence’ but by context — and cross reference with the same article in the Catholic Encyclopaedia which states it has ‘been observed since a remote period of antiquity’ — it must mean the first ten centuries of the existence of the clergy of the Catholic church and cannot mean the first ten centuries of the existence of the Law. This interpretation is supported by the authority of a maxim of law:

The law is from everlasting

God’s Law is from everlasting because God is from everlasting. Man’s legislation must have a date from which it takes effect.

a

‘I came not to judge the world, but to save it’

Footnotes

[1] ‘Ekklesia’ means ‘the congregation [of Christ]’. In this case, it refers to anyone following the Law of God. It is often wrongly translated as ‘church’ as in ‘You are Peter, the rock on which I will build my church’. This is more correctly translated as ‘You are Peter. You are the brick on which I will build my congregation.’ See Matthew 16:18

[2] It is therefore axiomatic that a legislative rule or statute requires the consent of an individual to its terms to carry the force of Law as a statute is a contractual offer.

[3] The Latin for ‘laws under the precedence of the Law’

[4] Black’s Law: ‘the reason for deciding’

[5] The case is also referred to as M’Alister v Stevenson

[6] , see Acts 5:29-39

[7] At one point, this ruling refers to the ‘laws of Babylon’, another term for commercial law going back 6,000 years

[8] Although you enter a court of law, you will be judged under the rules of equity rather than the Law unless you insist your Common Law rights

[9] This is of course a violation of the oath sworn by solicitors

[10] This establishes that there is a difference between ‘laws’ and ‘statutes’.

[11] Although not expressly stated in God’s Law, rights come from the duties set out in the Law. If you have a duty to love your neighbour, then you will automatically respect his right to, for example, privacy or free speech.

[12] http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09068a.htm

[13] http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09068a.htm

[14] These are the Article numbers for the revised version of Magna Carta. In the original of 1215, the rights quoted above were Articles 39 and 40.

[15] For office-holders who swear or affirm the oath see below.

[16] We have established that the Law of God takes precedence over ‘laws’. Where the two clash, the Queen would be bound under her oath to follow the Law of God.

[17] The Bible makes it clear that, once Christ has arrived, God will speak to man through him, the New Covenant as opposed to the Old Covenant in which God spoke to man through the prophets.

[18] Just because you have rights under the Law doesn’t mean you are obliged to use them. In any case, they remain your rights — used or not.

[20] Some have interpreted this as a prohibition on masturbation! It is amazing what perverted minds some people have.

[21] Your first port of call as the High Sheriff has a duty to the Law and delegates law enforcement to the Chief Constable of the County, http://www.highsheriffs.com/. Lord lieutenants can be found at: http://www.royal.gov.uk/TheRoyalHousehold/OfficialRoyalposts/LordLieutenants/LordLieutenants.aspx

[22] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniform_Commercial_Code

[23] The above material was previously found at http://www.constitutionpartypa.com/ucc_1-207___1-308.htm but the link has mysteriously disappeared. More can be found about the UCC at http://www.law.cornell.edu/ucc/1/, although this is not a complete version and rather bafflingly uses a different system of paragraph numbering.

Even here it is clear that the Common Law takes precedence: ‘A party that with explicit reservation of rights performs or promises performance or assents to performance in a manner demanded or offered by the other party does not thereby prejudice the rights reserved. Such words as ‘without prejudice,’ ‘under protest,’ or the like are sufficient’ (1-308, UCC).

[24] Black’s Law does not define ‘human being’

[25] The Oxford English Dictionary gives the root of the word person as ‘persona’ from Old English meaning ‘actor’s mask’.

[26] See Acts 10:34

[27] http://www.lonang.com/exlibris/blackstone/ Chapter 4 is particularly illuminating

[28] Our word ‘draconian’ for a harsh regime or policy comes from Draco.

[29] http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Gellius/11*.html.

[30] These maxims establish that law with a small ‘l’ is clearly not the same as the Law (of God)

[31] You can prove anything by selecting your evidence to fit your argument. A publication as prestigious as the Encyclopedia Britannica has proved itself to be as reliable as the tabloid press. Its editors should hang their heads in shame

[32] ‘Mammon’ is generally defined as the love or worship of money and material wealth. The latest translation of the Bible simply translates it as ‘money’.